Location: 17 km (11 mi) East of Bethlehem Map

Tel. (02) 277 3135

Open 8am- 5pm daily

No women allowed!

Mar Saba Monastery, also known as the Holy Lavra of Saint Sabbas the Sanctified, is one of the oldest continuously inhabited Christian monasteries in the world, located in the Kidron Valley (Wadi en-Nar) approximately 15 kilometers southeast of Jerusalem and 12 kilometers east of Bethlehem in the West Bank, Palestinian Territories. Perched dramatically on the cliffs of the Judean Desert, this Greek Orthodox monastery, founded in 483 CE by Saint Sabbas (Saba) the Sanctified, is renowned for its austere beauty, historical significance, and enduring spiritual legacy.

Foundation and Early History (5th–7th Centuries)

Mar Saba was

established by Saint Sabbas, a Cappadocian monk born in 439 CE, who

sought a life of asceticism in the Judean Desert. After training under

Saint Euthymius and living as a hermit in a cave near the Kidron Valley,

Sabbas founded the monastery in 483 CE as a lavra—a semi-eremitic

community where monks lived in individual cells during the week and

gathered for communal worship on weekends. The site was chosen for its

isolation, ideal for contemplation, and its proximity to water sources

in the valley.

By the late 5th century, Mar Saba grew into a

major center of monastic life, attracting monks from across the

Byzantine Empire. Sabbas established strict rules emphasizing prayer,

manual labor, and asceticism, which shaped the monastery’s enduring

traditions. He also founded other monasteries, earning him the title

“the Sanctified” for his contributions to Palestinian monasticism. In

492 CE, Sabbas was appointed archimandrite (leader) of all lavra

monasteries in Palestine by the Patriarch of Jerusalem, cementing Mar

Saba’s prominence.

The monastery faced challenges during the

Persian invasion of 614 CE, when Sassanid forces killed 44 monks and

damaged the complex. The monks’ skulls are still preserved in the Chapel

of the Martyrs, a testament to this massacre. Despite this, Mar Saba

recovered, and by the 7th century, it thrived as a theological and

intellectual hub.

Islamic and Crusader Periods (7th–13th

Centuries)

Following the Muslim conquest of the Levant in the 7th

century, Mar Saba operated under Islamic rule, generally with tolerance,

as monks paid the jizya tax for protection. The monastery’s isolation

helped preserve its autonomy, though periodic raids by Bedouin tribes

posed threats. During this period, Mar Saba produced significant

theological works, including those of Saint John of Damascus (676–749

CE), a monk who defended Christian iconography during the Byzantine

Iconoclastic Controversy and wrote influential treatises on theology and

philosophy.

The Crusader period (1099–1291) brought renewed

attention to Mar Saba as a pilgrimage site. Crusaders restored parts of

the monastery, and Western pilgrims, including knights and nobles,

visited, leaving graffiti still visible today. However, the monastery

remained under Greek Orthodox control, resisting Latin influence.

Mamluk and Ottoman Periods (13th–19th Centuries)

Under Mamluk

(1250–1517) and Ottoman (1517–1917) rule, Mar Saba faced financial

strain and occasional raids, but its monks maintained their traditions.

The monastery’s library grew, preserving ancient manuscripts, and its

reputation as a spiritual stronghold attracted pilgrims from the

Orthodox world, particularly from Greece, Georgia, and Russia. In the

14th century, Serbian monks resided at Mar Saba, contributing to its

multicultural community.

The 19th century saw modernization

efforts, including the construction of a new guesthouse in 1840 and

repairs to the fortifications. Russian pilgrims, in particular, provided

financial support, strengthening ties with the Russian Orthodox Church.

Modern Era (20th–21st Centuries)

Mar Saba survived the turbulent

20th century, including British Mandate rule (1917–1948), the

Arab-Israeli conflicts, and the establishment of the West Bank under

Jordanian (1948–1967) and later Israeli control (1967–present). Its

location in Area C of the West Bank, under full Israeli administration,

has complicated access, requiring coordination with military

checkpoints.

In 2012, Mar Saba was added to UNESCO’s tentative

list of World Heritage Sites for its cultural and historical

significance. Today, it remains a functioning monastery, home to a small

community of Greek Orthodox monks, and a destination for pilgrims and

tourists, though access is restricted to men due to monastic rules.

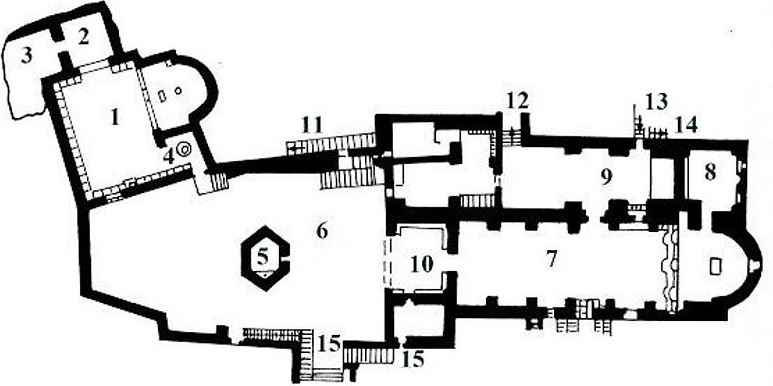

1. Church of Saint Nicholas

2. Treasury

3. Ossuary

4. Baptistery

5. Chapel, resting place of Saint Sava

(Saba)

6. Courtyard with burial loculi

7. Cathedral of

the Annunciation

8. Treasury

9. North Chapel

10.

Narthex

11.Staircase to the upper entrance of the

monastery

12. Passageway to the North part of the

monastery

13. Staircase to the refectory

14. Staircase

to the lookout

15. Passageway to the South cells

Mar Saba’s architecture reflects its adaptation to the harsh desert

environment and its long history of expansion and repair. The monastery

clings to the steep cliffs of the Kidron Valley, with buildings

constructed from local limestone, blending seamlessly into the

landscape. Its fortified appearance, with high walls and towers, was

designed to protect against raids.

Key Features

Main Church

(Katholikon): Dedicated to Saint Sabbas, the central church features

Byzantine-style frescoes, icons, and a marble floor. It houses the tomb

of Saint Sabbas, a focal point for veneration. The church’s dome and

bell tower are iconic elements visible from a distance.

Chapel of the

Martyrs: A small chapel commemorates the monks killed in 614 CE,

displaying their skulls in a glass case as relics.

Monks’ Cells:

Scattered across the cliffs, many cells are built into natural caves,

reflecting the lavra’s original eremitic character. Modern cells within

the compound are simple, with minimal furnishings.

Library and

Scriptorium: The library contains over 3,000 ancient manuscripts,

including biblical texts, theological works, and hymns, some dating to

the 5th century. The scriptorium was a center for copying manuscripts,

particularly during the Byzantine and early Islamic periods.

Fortifications: The monastery’s walls, reinforced over centuries,

include watchtowers and a main gate. The “Women’s Tower” (Toupha), a

separate structure across the valley, was built in the 19th century to

house female pilgrims, as women are not permitted inside the main

complex.

Water Cisterns: Underground cisterns collect rainwater,

ensuring self-sufficiency in the arid environment.

Refectory and

Kitchen: The dining hall is modest, reflecting the monks’ ascetic

lifestyle, with meals prepared in a traditional kitchen using local

ingredients.

The monastery’s layout is irregular, shaped by the

terrain, with narrow stairways and passages connecting buildings. Its

aesthetic—rugged stone against the desert cliffs—evokes a sense of

timelessness and spiritual retreat.

Mar Saba is a cornerstone of Christian monasticism, particularly

within the Greek Orthodox tradition. Its significance stems from several

factors:

Spiritual Legacy

Saint Sabbas’ Rule: Sabbas’ monastic

rule, emphasizing solitude, communal worship, and manual labor,

influenced Orthodox monasticism worldwide. His Typikon (liturgical and

administrative guidelines) is still followed at Mar Saba and other

monasteries.

Theological Contributions: Monks like Saint John of

Damascus produced works that shaped Christian doctrine, particularly on

the veneration of icons and the nature of Christ. The monastery’s

scriptorium preserved Greek, Aramaic, and Arabic texts, bridging

Byzantine and Islamic intellectual traditions.

Pilgrimage

Destination: Mar Saba attracts Orthodox pilgrims, especially during the

feast of Saint Sabbas (December 5), when liturgies draw monks and

visitors from Jerusalem and beyond.

Cultural Impact

Multicultural History: Mar Saba hosted monks from diverse regions,

including Cappadocia, Syria, Georgia, Serbia, and Russia, fostering

cultural exchange. Its manuscripts reflect this diversity, with texts in

multiple languages.

Art and Iconography: The monastery’s frescoes and

icons, though faded, are examples of Byzantine art, depicting saints,

biblical scenes, and geometric patterns. The iconostasis in the main

church is particularly revered.

Preservation of Tradition: Mar Saba’s

adherence to ancient practices, such as the Julian calendar and

all-night vigils, makes it a living museum of early Christian

monasticism.

Daily Life at Mar Saba

The monastery is home to

approximately 10–15 monks, a significant decline from its peak of over

150 in the Byzantine era. The monks, primarily Greek and Palestinian,

follow a rigorous schedule rooted in prayer and labor:

Prayer:

The day begins with the Midnight Office (around 2:00 AM), followed by

Matins, the Divine Liturgy, and other services, totaling up to 8 hours

of prayer daily. Services are conducted in Greek, with some Arabic

elements.

Manual Labor: Monks maintain the monastery, tend a small

garden, produce candles and incense, and preserve manuscripts. Some

engage in icon painting or hospitality for visitors.

Ascetic

Practices: Meals are simple, typically consisting of bread, olives,

vegetables, and occasional fish, with fasting observed on most days.

Monks live in sparse cells, emphasizing detachment from material

comforts.

Hospitality: Male pilgrims and visitors are welcomed, often

offered tea or coffee, but must adhere to strict rules, including

silence during services and modest attire.

The monks’ isolation

fosters contemplation, though they maintain contact with the

Patriarchate of Jerusalem and occasionally travel for religious duties.

Access and Restrictions

Gender Restriction: Women are not

permitted inside Mar Saba, a rule rooted in its all-male monastic

tradition. Female visitors can view the monastery from the Women’s Tower

or nearby viewpoints.

Location: Situated in Area C of the West Bank,

access requires passing Israeli military checkpoints. Visitors need

passports and must coordinate with the monastery, as it is not always

open to tourists.

Transportation: From Jerusalem or Bethlehem, taxis

or private vehicles are the primary means of reaching Mar Saba, as

public transport is limited. The road is paved but winding, with

stunning desert views.

Preservation

Conservation Efforts: The

monastery faces challenges from natural erosion, humidity affecting

manuscripts, and limited funding for restoration. International

organizations, including UNESCO, have supported preservation efforts,

particularly for the library.

Tourism: While tourism boosts

awareness, it strains the monks’ resources and disrupts their solitude.

Guided tours, often arranged through Jerusalem or Bethlehem agencies,

are recommended to respect monastic life.

Geopolitical Context

Mar Saba’s location in the West Bank places it in a politically

sensitive area. The monastery maintains neutrality, focusing on its

spiritual mission, but regional tensions can affect visitor numbers and

access.

For those planning a visit:

Hours: The monastery is typically open

to male visitors from 9:00 AM to 3:00 PM, though hours vary. It is

closed during major Orthodox feasts and Lent.

Dress Code: Modest

clothing (long sleeves, pants) is required, and photography inside the

church is prohibited.

Highlights: Key sites include the main church,

the Chapel of the Martyrs, and the cliffside views. The library is not

open to the public but may be discussed by guides.

Tips: Bring water,

sunscreen, and sturdy shoes, as the terrain is rugged. Respect the

monks’ silence and avoid loud behavior.

Excavations around Mar Saba, particularly in the 20th century, uncovered Byzantine-era artifacts, including pottery, coins, and mosaic fragments, confirming its early history. The monastery’s library remains a treasure trove, with ongoing efforts to digitize manuscripts for global access. In 2015, a rare 6th-century manuscript of the Gospel of Mark was identified, highlighting Mar Saba’s role in preserving early Christian texts.