Location: The Burren

Constructed: c. 1480

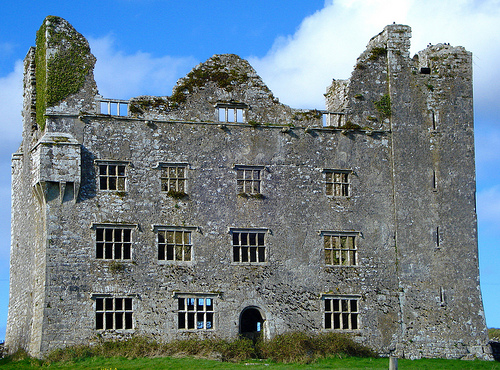

Leamaneh Castle, located in the townland of Leamaneh North, Kilnaboy parish, County Clare, Ireland, is a ruined but evocative structure on the edge of the Burren National Park, near the intersection of the R476 and R480 roads between Corofin and Kilfenora. Comprising a 15th-century tower house and a 17th-century manor house, this National Monument is celebrated for its architectural duality, turbulent history, and the infamous legend of Máire Rua O’Brien (Red Mary), a figure whose fiery reputation and ghostly presence dominate its lore. Managed by the Office of Public Works (OPW), the castle is on private land and inaccessible to the public due to safety concerns, but its striking ruins can be admired from the roadside.

Leamaneh Castle’s history spans over five centuries, reflecting

Ireland’s complex interplay of Gaelic, Norman, and English influences,

with its story shaped by the powerful O’Brien family and the

controversial figure of Máire Rua.

Origins (Late 15th Century):

The castle began as a five-story tower house constructed around

1480–1490, likely by Toirdhealbhach Donn Ó Briain, a member of the

O’Brien family, descendants of Brian Boru and one of the last High Kings

of Thomond. The name “Leamaneh,” derived from the Irish léim an éich

(“the horse’s leap”) or possibly léim an fheidh (“the deer’s leap”), may

refer to a local geographical feature or legend, though its exact origin

is unclear. The O’Briens, prominent in Clare, built the tower at a

strategic crossroads where the baronies of Burren, Corcomroe, and

Inchiquin met, controlling regional trade and defense. In 1550, the

castle was granted to Donough O’Brien, who was later executed in

Limerick in 1582 for rebellion during the Mac an Iarla War, highlighting

the family’s fraught relationship with English authority.

Máire Rua

and Expansion (1630s–1650s): The castle’s most defining era began in

1639 when Conor O’Brien, a descendant of Donough, married Máire ní Mahon

(MacMahon), known as Máire Rua or “Red Mary” for her red hair and

reputed fiery temperament. Máire, born c. 1615 to Sir Turlough O’Brien

and Lady Honora, inherited significant wealth from her first husband,

Daniel Neylan (or O’Neillan) of Dysert O’Dea Castle, with whom she had

three sons. Her £1,000 dowry funded major expansions, transforming

Leamaneh into one of Ireland’s grandest residences. In 1648, Conor and

Máire added a four-story manor house with large mullioned windows, a

stark contrast to the defensive tower. The couple were staunch

Confederate supporters during the Eleven Years’ War (1641–1653),

opposing Cromwellian forces and raiding English settlers. In 1651, Conor

was mortally wounded by General Henry Ireton’s forces at Inchicronan.

Legend claims Máire callously refused him entry, shouting, “What do I

want with dead men here?” though she reportedly nursed him until his

death hours later.

Cromwellian Era and Máire’s Strategy (1650s–1686):

To preserve her estate from Cromwellian confiscation, Máire married

Cornet John Cooper, a Cromwellian officer, shortly after Conor’s death,

a pragmatic move that secured Leamaneh for her son Donough (later Sir

Donat). This third marriage, producing one child, allowed Máire to

navigate the turbulent 1650s, with Cromwellian troops occasionally

garrisoned at the castle for its strategic strength, as noted by General

Edmund Ludlow. Cooper amassed wealth through land speculation but faced

financial ruin, mortgaging Leamaneh to cover debts. Máire’s reputation

grew notorious, with folklore alleging she had up to 25 husbands,

divorcing or killing them after a year and a day, though historical

records confirm only three. Stories of her cruelty—hanging male servants

by their necks and female servants by their hair, or challenging guests

to ride a wild stallion to their deaths at the Cliffs of Moher—are

likely exaggerated, reflecting misogynistic tropes about powerful women.

Máire died in 1686, possibly at Leamaneh, though her burial site is

unknown, with some suggesting Coad Church in Kilnaboy.

Decline and

Abandonment (1686–18th Century): Donough O’Brien, raised Protestant

unlike his Catholic half-siblings, inherited Leamaneh but found it

dilapidated by 1684–1685. He relocated the family seat to Dromoland

Castle in Newmarket-on-Fergus, a larger, more modern estate. Donough,

who became the “richest commoner in Ireland,” served as Sheriff of Clare

(1690) and MP for Clare (1695–1713), building “Sir Donat’s Road,” a toll

road linking Kilnaboy to Leamaneh, parts of which survive. Leamaneh was

abandoned by the early 18th century, falling into ruin as the O’Flaherty

family, who gained it through marriage, faced financial decline. The

castle’s strategic value waned, and nature reclaimed the site.

Modern

Era: By the 19th century, Leamaneh was a picturesque ruin, inspiring

paintings, photographs, and folklore. In 1906 or 1908, its

barbican-style gates were relocated to Dromoland Castle by Lord

Inchiquin, and a fireplace was moved to the Old Ground Hotel in Ennis.

Designated a National Monument under the National Monuments Acts

1930–2014, the OPW has stabilized the ruins, repointing stone walls and

removing vegetation to prevent further decay. However, its poor

condition prevents public access, and it remains on private agricultural

land.

The historical record is robust for the O’Brien era,

particularly Máire Rua’s life, but folklore, such as the 25 husbands or

stallion legend, lacks corroboration and likely stems from 19th-century

oral traditions, possibly amplified to demonize a powerful woman. The

crannóg mentioned in some sources is speculative, as no archaeological

evidence confirms its proximity. The castle’s role in the Cromwellian

wars is well-documented, but details of Máire’s interactions with Ludlow

and Cooper’s death (natural, accidental, or violent) are ambiguous,

reflecting gaps in primary sources.

Leamaneh Castle is a rare architectural hybrid, combining a

15th-century defensive tower house with a 17th-century manor house,

showcasing both martial and residential priorities. Its ruins,

though roofless, retain significant features that highlight its

historical evolution.

Structure:

15th-Century Tower House:

The original structure, built c. 1480–1490, is a five-story

rectangular tower, approximately 15 meters high, constructed from

local limestone. Typical of Irish tower houses, it features:

Arrow Slits: Narrow loops for archers, emphasizing defense.

Spiral Staircase: A stone staircase within the thick walls,

providing access to upper floors.

Small Chambers: Cramped rooms

for storage, defense, or minimal living space.

Corbels: Stone

brackets, later associated with Máire Rua’s alleged punishments,

though this is likely apocryphal.

17th-Century Manor House: Added

in 1648 by Conor O’Brien and Máire Rua, the four-story manor adjoins

the tower’s west side, forming an L-shaped complex. It includes:

Mullioned and Transomed Windows: Large, decorative windows, unusual

for Ireland’s conflict-ridden 1640s, reflecting wealth and a shift

to residential comfort. The upper floors’ smaller windows create a

trompe-l’œil effect, making the building appear taller from the

ground.

Gabled Roofline: Now collapsed, the manor’s gables were a

Renaissance-inspired feature, contrasting with the tower’s

austerity.

Separate Entrance and Offices: The ground floor housed

a kitchen and service areas, with living quarters above, indicating

a manor house layout.

Bawn and Outbuildings: A walled courtyard

(bawn) with a barbican-style gateway, now at Dromoland Castle,

protected the complex. Remnants of walled gardens, a deer park, and

outbuildings are visible, suggesting a once-extensive estate.

Defensive Features: The tower’s thick walls, arrow slits, and

elevated entrance (likely with a murder-hole, though not explicitly

documented) reflect 15th-century defensive needs. The manor’s large

windows, however, indicate reduced defensive concerns by the 1640s,

a risky choice during the Confederate Wars.

Current State: The

castle is roofless, with the manor’s four walls and the tower’s

shell intact. Vegetation has been cleared, and stonework repointed,

but the structure is unstable, with collapsed interiors and no

accessible floors. The juxtaposition of the tower’s narrow slits and

the manor’s elegant windows creates a striking visual contrast,

highlighting its architectural evolution.

The architectural

narrative is well-supported, with the tower-manor duality a rare

feature in Ireland, akin to Bunratty Castle’s later expansions. The

trompe-l’œil effect is documented, but claims of a “grandest” status

may exaggerate, as Dromoland and Bunratty were larger. The absence

of interior access limits detailed study, and some sources’ mention

of a “partially demolished” tower during manor construction lacks

archaeological confirmation.

Leamaneh Castle’s significance lies in its embodiment of Ireland’s

socio-political shifts, its O’Brien legacy, and its haunting folklore,

particularly surrounding Máire Rua.

O’Brien Dynasty: As a

stronghold of the O’Briens, descendants of Brian Boru, Leamaneh

represents their enduring influence in Clare. Their pledge to Henry VIII

in the 1500s, earning titles like Earl of Thomond, reflects the

Gaelic-Norman synthesis, while their Confederate allegiance in the 1640s

underscores resistance to English rule. Donough’s move to Dromoland and

Protestant upbringing highlight the family’s adaptation to English

governance, securing wealth and status.

Máire Rua’s Legend: Máire Rua

is Leamaneh’s cultural heart, her red-haired ghost cementing its status

as one of Ireland’s most haunted castles. Folklore paints her as a

ruthless tyrant—hanging servants, killing husbands, and tricking riders

to their deaths at the Cliffs of Moher—yet these tales likely exaggerate

her agency to vilify a wealthy, independent woman. Her strategic

marriage to John Cooper, however, is factual, showcasing her political

acumen in preserving her estate. Stories of her death in a hollow tree,

possibly at Leamaneh or a “Druid’s Altar,” are unverified but fuel her

spectral reputation, attracting paranormal enthusiasts, especially on

Halloween.

Artistic Legacy: The castle’s ruins have inspired

paintings, photographs (e.g., Jerzy Strzelecki’s 1989 image), and

literary accounts since the 19th century. Its stark beauty in the

Burren’s karst landscape has made it a subject for artists like James A.

Truett, who documented its avian inhabitants. The 2015 and 2019

photographs by LawrenceCollection highlight its enduring visual appeal.

National Monument Status: As a National Monument, Leamaneh underscores

Ireland’s commitment to preserving its medieval heritage, though its

private ownership and ruinous state limit its public role compared to

restored sites like Bunratty. Its inclusion in Burren tourism

itineraries reflects its regional importance, tying it to nearby sites

like Poulnabrone Dolmen and Aillwee Cave.

The Máire Rua folklore,

while culturally rich, risks overshadowing the castle’s historical role,

with sources like Dúchas’ collection amplifying unverified tales. The

O’Brien narrative is robust, but the castle’s later O’Flaherty phase is

less documented, suggesting a need for further research. The “horse’s

leap” etymology is plausible but folkloric, possibly linked to Máire’s

stallion legend rather than geography.

Leamaneh Castle is a non-accessible National Monument on private

agricultural land, managed by the OPW, with no formal tours or interior

entry due to safety concerns. Its roadside visibility makes it a

compelling stop for passersby in the Burren.

Location and Access:

Address: Leamaneh North, Kilnaboy, Co. Clare, Ireland (GPS: 52.987811,

-9.139944).

Directions: Located at the R476/R480 intersection, 6.2 km

east of Kilfenora, 10 km from Corofin, and 30 km from Ennis. From Dublin

(2.5–3 hours, 230 km), take the M6/N18 to Ennis, then R476 northwest

through Corofin and Kilnaboy. From Galway (1 hour, 50 km), use the

N18/R476. The castle is visible on the left along the R480.

Public

Transport: Limited options exist. Bus Éireann routes from Ennis to

Corofin (30 minutes) or Galway to Kilfenora require a taxi or 2–3 km

walk to the site. Ennis Train Station (40 minutes’ drive) connects to

Dublin and Galway.

Parking: A small gravel pull-off at the R476/R480

intersection accommodates 1–2 cars, though roadside parking is cramped

and requires caution due to traffic.

Visitor Experience:

Access: The castle is not open to the public, as it is on private land

and structurally unsafe. Visitors can view it from the roadside, taking

photos of the tower and manor’s facade. Trespassing is discouraged, and

the OPW warns of liability for injuries, emphasizing care.

Duration:

A visit typically lasts 10–30 minutes, sufficient to admire the ruins,

read about Máire Rua (via guidebooks or apps), and photograph the Burren

backdrop. TripAdvisor reviews (4.5/5) praise its “impressive” and

“unique” structure but advise against detours unless nearby, given the

lack of interior access.

Features: The ruins’ tower-manor contrast,

mullioned windows, and Burren setting are photogenic, especially at

dusk. Birds nesting in the ruins, noted by James A. Truett, add a lively

touch. The absence of graffiti, as one reviewer noted, reflects Irish

respect for heritage.

Nearby Attractions: Leamaneh integrates with

Burren itineraries:

Poulnabrone Dolmen (10 km, 15 minutes), a

Neolithic tomb.

Caherconnell Stone Fort (8 km), with sheepdog

demonstrations.

Aillwee Cave (15 km), a karst cave with a tea room.

Cliffs of Moher (25 km, 25 minutes), Ireland’s iconic cliffs.

Doolin

and Lahinch, for music and surfing.

Dining and Amenities: No

facilities exist at the site. Nearby Kilfenora (6 km) offers pubs like

Vaughan’s or Linnane’s, while Corofin and Ennis provide restaurants

(e.g., China Palace, ZAIQA). Accommodation options include hotels in

Ennis or B&Bs in the Burren.

Tips for Visitors:

Use GPS for

accuracy, as one visitor reported confusion in Kilnaboy due to poor map

reading. From Ennis, take R476 to R480; the castle is on the left.

Bring a guidebook (e.g., O’Keeffe’s Burren guide) or access online

resources like Heritage Ireland for history, as no on-site signage

exists.

Visit in spring or autumn for mild weather and vivid Burren

landscapes; avoid wet seasons for safer parking.

Combine with Burren

attractions for a half-day itinerary, starting at Poulnabrone or

Caherconnell.

Respect private property; do not climb fences or

approach the ruins closely.

Challenges:

Inaccessibility: The

lack of interior access disappoints some, with TripAdvisor noting it’s

“not worth a detour” unless passing by. Permission from the landowner is

rarely granted.

Parking: The small pull-off and busy roads pose

risks, especially for larger groups.

Interpretation: No on-site

guides or plaques limit understanding, relying on external resources.

Folklore vs. Fact: Máire Rua’s exaggerated tales can overshadow the

castle’s historical role, requiring visitors to discern myth from

reality.

The visitor experience is modest but rewarding for those

intrigued by ruins and legends, though its private status and ruinous

condition contrast with accessible sites like Bunratty.

Tower-Manor Duality: The 15th-century tower’s defensive slits

juxtaposed with the 17th-century manor’s mullioned windows create a

unique architectural narrative.

Trompe-l’œil Windows: The manor’s

smaller upper windows enhance its perceived height, a Renaissance

flourish.

Máire Rua’s Legacy: The castle’s haunting reputation, tied

to Red Mary’s ghost, adds cultural allure, with reported sightings at

the castle and a “Druid’s Altar.”

Burren Setting: The stark karst

landscape frames the ruins, enhancing their dramatic presence.

Relocated Elements: The barbican gates at Dromoland and fireplace at the

Old Ground Hotel connect Leamaneh to broader Clare heritage.

Leamaneh Castle fits Ireland’s tradition of tower houses (e.g., Oranmore, Tyrrellspass) and fortified manors, reflecting the O’Briens’ dual role as Gaelic lords and English-aligned elites. Its Confederate resistance mirrors Roscommon Castle’s role, while Máire Rua’s pragmatism echoes strategies seen at Springfield Castle. The manor’s decorative windows, rare for 1640s Ireland, highlight a fleeting prosperity amidst war, akin to Malby’s renovations at Roscommon. The castle’s ruinous state, like many post-Cromwellian sites, underscores English efforts to dismantle Irish strongholds. Its haunting folklore aligns with Thoor Ballylee’s poetic mystique, though Leamaneh’s isolation and inaccessibility make it a rawer experience. As a National Monument, it contributes to the Burren’s UNESCO Global Geopark status, though its tourism potential is underexploited compared to Newgrange or Blarney.

Preserving Leamaneh Castle balances conservation with its private

status and ruinous condition:

Structural Decay: The roofless

manor and weathered tower risk further collapse. The OPW’s repointing

and vegetation removal are ongoing, but full restoration is unfeasible

due to cost and historical integrity concerns.

Private Ownership: The

agricultural land’s use limits public access, frustrating visitors and

historians. Negotiations for limited access could enhance tourism, as at

Poulnabrone.

Weathering and Environment: The Burren’s harsh climate

accelerates stone erosion, though the karst landscape preserves the

site’s stark beauty.

Folklore Overload: Máire Rua’s exaggerated

tales, while engaging, can obscure the castle’s broader history,

requiring careful interpretation by guides or resources.

Funding: As

a National Monument, OPW maintenance is state-funded, but budget

constraints prioritize stabilization over visitor amenities, unlike

commercialized castles.

The castle’s preservation is adequate for its

ruinous status, but its potential as a cultural hub is limited by access

restrictions and underinvestment in interpretation.