Location: Studley Royal Estate, 3 km (2 mi) Southwest of Ripon, North Yorkshire Map

Tel. 01756 608888

Open:

Mar- Oct 10am- 5pm daily

Nov- Jan 10am- 4pm Sat- Thu

Feb 10am- 4pm daily

Official site

Fountains Abbey is one of the largest and best-preserved ruined Cistercian monasteries in England, located in the valley of the River Skell near Ripon in North Yorkshire. Founded in 1132, it operated for over 400 years until its dissolution in 1539 under Henry VIII's orders. Today, the abbey ruins form the centerpiece of Studley Royal Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site recognized for its outstanding universal value as a masterpiece of human creative genius and an exceptional example of monastic and landscape architecture. The site, owned by the National Trust and maintained by English Heritage, spans approximately 70 acres and attracts visitors for its historical, architectural, and natural significance.

Founding and Early Development

The abbey's origins trace back

to a revolt in 1132 at St Mary's Abbey in York, a Benedictine

monastery, where 13 reform-minded monks were expelled for seeking a

stricter adherence to the Rule of St Benedict. Led by figures like

Prior Richard and including Saint Robert of Newminster, they sought

refuge under Archbishop Thurstan of York, who granted them land in

the sheltered Skell Valley—abundant with natural resources like

stone, wood, and springs (from which the name "Fountains" derives).

Initially living in extreme poverty, the monks endured a harsh

winter in 1133 before affiliating with the Cistercian order in 1135,

becoming the second Cistercian house in northern England after

Rievaulx Abbey. They were placed under the authority of Clairvaux

Abbey in France, with guidance from St Bernard of Clairvaux.

Geoffrey of Ainai, a monk from Clairvaux, instructed them in

Cistercian customs, including the observance of the Canonical Hours

and the construction of initial wooden buildings.

By the mid-12th

century, under Abbot Henry Murdac (1143–1147), the abbey began

replacing timber structures with stone. A simple stone church and

cloister were built, and the community expanded rapidly, founding

daughter houses and attracting novices. However, in 1146, the abbey

faced a violent attack from supporters of William FitzHerbert, whom

Murdac opposed as Archbishop of York; the mob burned most buildings

except the church. Recovery was swift, with repairs and expansions

continuing under subsequent abbots like Richard (1150–1170), who

oversaw the completion of the chapter house and much of the church.

Period of Prosperity and Challenges

The late 12th and early

13th centuries marked a golden age for Fountains Abbey, which became

one of England's wealthiest monasteries through sheep farming, wool

trade, and land acquisitions. Abbots such as Robert of Pipewell

(1170–1180) and Ralph Haget (1190–1203) managed charitable efforts,

including aid during the 1194 famine. The abbey supported a large

community of choir monks and lay brothers, with the latter handling

agricultural and industrial labors.

Decline set in during the

14th century due to economic pressures, including over-reliance on

wool futures, Scottish raids, heavy taxation, and the Black Death

(1348–1349), which halved the population and strained resources. The

Papal Schism (1378–1409) led to a temporary break from the

Cistercian motherhouse at Cîteaux, forming an independent English

Cistercian chapter. Internal strife, such as the disputed abbot

election of 1410–1416, further weakened the abbey. Revival efforts

under abbots like John Greenwell (1442–1471) and Marmaduke Huby

(1495–1526) included building projects and increasing monk numbers

to around 60, but scandals under William Thirsk (1526–1536) hastened

its end.

Dissolution and Post-Monastic Era

In 1539, during

the Dissolution of the Monasteries, Abbot Marmaduke Bradley

surrendered the abbey to the Crown, which seized its assets—valued

at over £1,000 annually—and sold the property in 1540 to Sir Richard

Gresham. The site passed through owners like Sir Stephen Proctor,

who built Fountains Hall around 1597 using abbey stone, and the

Messenger family (1627–1767). In 1767, William Aislabie integrated

it into the adjacent Studley Royal Estate, creating a unified

landscape garden. The ruins were preserved as a romantic folly

within this Georgian water garden, enhancing its picturesque appeal.

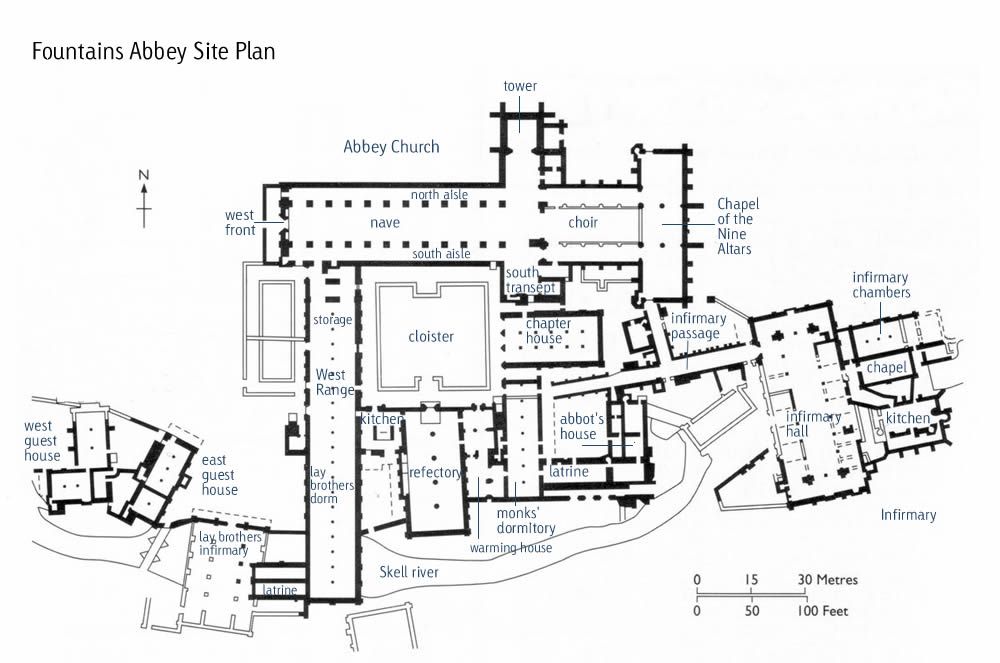

Fountains Abbey exemplifies Cistercian architecture, emphasizing

simplicity, functionality, and harmony with nature. The precinct is

divided by the River Skell into three zones: the central monastic

core (church and cloister), the inner court (domestic buildings),

and the outer court (industrial areas). Enclosed by a 13th-century

perimeter wall, the site features a strategic layout with the river

providing water power for mills.

The abbey church, rebuilt after

the 1146 fire and completed around 1170, measures about 300 feet

long with an 11-bay aisled nave, transepts, and a presbytery

extended in the 13th century. Its design draws influences from

Durham Cathedral and Beverley Minster, with a lantern tower over the

crossing and pointed arches in the choir. Notable additions include

Huby's Tower (c. 1495–1526), a 160-foot perpendicular Gothic

structure at the north transept, inscribed with the motto "Soli Deo

Honor et Gloria" (Honor and Glory to God Alone).

The cloister,

measuring 125 feet square, features arcading in black marble and

white sandstone, connecting key buildings: the chapter house (for

daily meetings), parlour, warming house (with fireplaces for

winter), refectory (dining hall with pulpit for readings), and

kitchens. Lay brothers' quarters include a large refectory and

reredorter (latrine block) over the river for sanitation. Industrial

features south of the river include a wool house, tannery, and water

mills, reflecting the abbey's self-sufficiency.

The ruins today

are remarkably intact, with standing walls up to full height in

places, allowing visitors to visualize monastic life—from prayer in

the church to communal activities in the cloister.

Cistercian life at Fountains emphasized austerity, manual labor, and prayer. Monks followed a rigorous schedule of eight daily services (Matins to Compline), interspersed with work in fields, scriptorium, or workshops. Lay brothers, often illiterate, handled practical tasks, enabling choir monks to focus on spiritual duties. The abbey was vegetarian, with fish from on-site ponds, and silent except during chapter meetings. Its wealth supported hospitality for travelers and the poor, aligning with Cistercian ideals of charity.

As a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1986 (under the name Studley Royal Park including the Ruins of Fountains Abbey), the site illustrates the evolution of monasticism and 18th-century landscape design. It represents the Cistercians' impact on medieval England, with the ruins among Europe's most significant monastic remains. Preservation efforts by the National Trust and English Heritage include conservation of structures, landscape management, and educational programs. The site's integration with Studley Royal's water gardens—featuring canals, ponds, and follies—creates a harmonious blend of ruin and nature, influencing Romanticism.

Studley Royal Water Garden: An 18th-century Georgian landscape

designed by John and William Aislabie, with formal water features,

temples, and vistas framing the abbey ruins.

Fountains Hall: A

Jacobean mansion built c. 1598–1611 from abbey stone, now housing

exhibitions like contemporary art installations.

St Mary's

Church: A Victorian Gothic Revival church (1871–1878) on the estate,

adding to the site's ecclesiastical heritage.

Managed by the National Trust, the site is a popular attraction open year-round (check website for exact times), with features like guided tours, floodlit evening visits ("Fountains by Floodlight"), and events such as art installations (e.g., Luke Jerram's "Helios" sun sculpture in the ruins). It's dog-friendly, accessible with mobility aids, and supports education through school visits. Wildlife thrives in the gardens, which burst with autumn colors, and conservation focuses on protecting the historic fabric and biodiversity. Admission is via National Trust membership or tickets, contributing to ongoing preservation.