Location: Cayo District Map

Baking Pot is a major Maya archaeological site in the Belize River Valley, known for its extensive urban settlement, monumental architecture, and long occupational history spanning from the Preclassic to Postclassic periods (approximately 600 BC to AD 1000). Located in the Cayo District, it is one of the largest Maya centers in the region, alongside sites like Xunantunich and Cahal Pech. Despite its historical importance, Baking Pot remains less visited than Belize’s more famous ruins, offering a quieter, more authentic experience for archaeology enthusiasts, researchers, and adventurous travelers. Its name, possibly derived from a colonial-era term for a riverside clay deposit or a local landmark, reflects its setting along the Belize River.

Baking Pot lies in the fertile Belize River Valley, approximately 6

miles (10 km) east of San Ignacio, the Cayo District’s main town, and

about 2 miles (3 km) south of the George Price Highway (formerly Western

Highway) near the village of Spanish Lookout. The site is accessible via

a short dirt road from the highway, making it reachable by car or guided

tour from San Ignacio or Belmopan (20 miles away). Its coordinates are

roughly 17°11′N, 89°01′W.

The site’s geography is defined by:

Belize River: Baking Pot sits on the southern bank of this slow-moving,

meandering river, which provided water, fertile soils, and a trade route

for the ancient Maya. The river’s alluvial plains supported intensive

agriculture, key to the city’s growth.

Tropical Lowlands: The

surrounding landscape is a mix of broadleaf rainforest and savanna, with

mahogany, ceiba, and cohune palm trees. Wildlife includes howler

monkeys, agoutis, jaguars (rare), and over 200 bird species, such as

toucans and oropendolas.

Limestone Terraces: The site is built on

gently rolling terrain, with natural limestone ridges shaped into

terraces and platforms for buildings. Nearby karst hills, part of the

Maya Mountains’ foothills, contain caves used for Maya rituals.

Agricultural Fields: Raised fields and drainage systems around Baking

Pot indicate sophisticated farming, supporting a dense population.

The climate is tropical, with temperatures of 80–90°F and high humidity.

The dry season (February–May) offers easier access and clearer views,

while the wet season (June–November) brings lush greenery but muddy

trails.

Baking Pot was a thriving Maya city with a continuous occupation from

the Middle Preclassic (ca. 600 BC) to the Postclassic (ca. AD 1000),

peaking during the Late Classic (AD 600–850). It served as a political,

economic, and ceremonial hub in the Belize River Valley, likely

interacting with larger centers like Tikal (Guatemala) and Caracol

(Belize). Archaeological evidence, primarily from excavations by the

Belize Valley Archaeological Reconnaissance Project (BVAR) since the

1990s, reveals a complex urban society.

Key historical features

include:

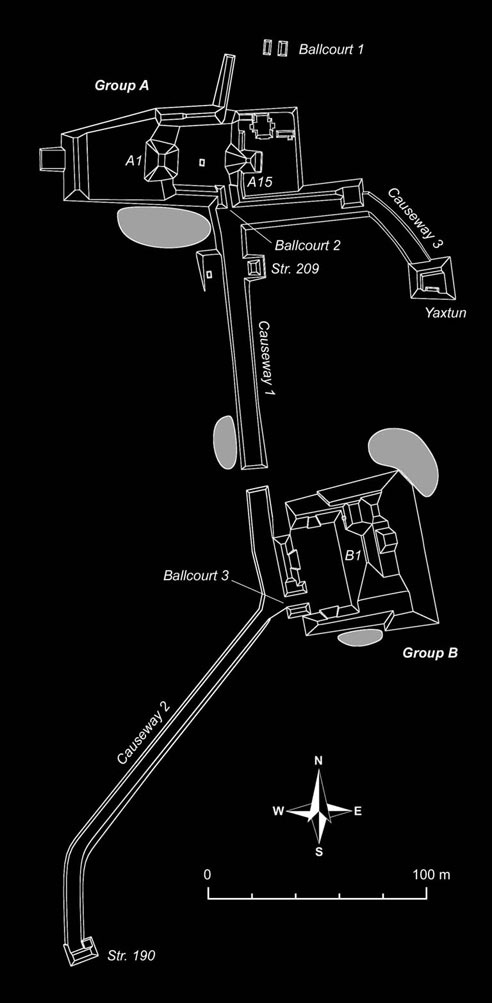

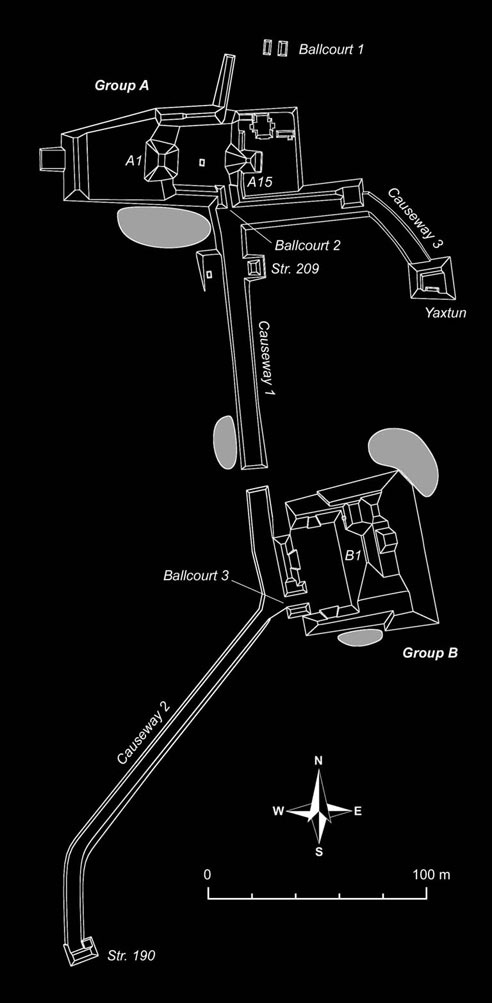

Urban Layout: Baking Pot spans several square kilometers,

with a central core of monumental architecture surrounded by residential

zones, causeways, and agricultural fields. The core includes two main

groups (Group A and Group B), connected by a sacbe (elevated causeway),

and numerous smaller plazas and hamlets.

Monumental Architecture:

Group A: Features a large plaza with pyramids, temples, and elite

residences. The tallest structure, a partially restored pyramid, reaches

about 33 feet (10 meters), offering views of the valley.

Group B:

Includes a royal palace complex and a ballcourt, a hallmark of Maya

cities where ritual games symbolized cosmic battles. The ballcourt’s

markers and rings are partially intact.

Eastern Shrine: A distinctive

feature, this tomb-like structure in Group A contained elite burials

with jade, obsidian, and ceramic offerings, suggesting ancestor worship.

Stelae and Altars: Unlike Nim Li Punit or Xnaheb, Baking Pot has fewer

carved stelae, but plain stelae and altars mark ceremonial spaces,

possibly commemorating rulers or events.

Causeways: Three sacbeob

(causeways) link the core to outlying groups, facilitating trade and

processions. The longest stretches over 1 km, connecting to a

residential hamlet.

Burials and Artifacts: Excavations uncovered

royal tombs with polychrome pottery, jade jewelry, and stingray spines

(used in bloodletting rituals). A notable find from 2017 revealed a Late

Classic elite burial with over 200 ceramic vessels, indicating wealth

and status.

The Maya at Baking Pot practiced a mix of agriculture,

trade, and ritual. They grew maize, beans, cacao, and squash, using

raised fields and terraces to manage flooding. The Belize River linked

them to coastal trade routes, exchanging obsidian, salt, and shells with

distant cities. Ritually, Baking Pot’s caves and shrines were portals to

Xibalba (the underworld), where offerings honored deities like Chac

(rain god) and K’awiil (sustenance god).

Culturally, Baking Pot

reflects Belize’s modern diversity—Q’eqchi’ and Mopan Maya, Creole,

Mestizo, and Mennonite communities live nearby, especially in Spanish

Lookout, a Mennonite farming hub. English, the official language, is

spoken alongside Belizean Kriol and Spanish, with Maya languages in

rural areas. Local guides often share oral histories, connecting Baking

Pot to living Maya traditions like cacao ceremonies or milpa farming.

Baking Pot has been studied intermittently since the early 20th

century, with significant work by:

Gordon Willey (1950s): Early

surveys mapped the site’s core, noting its agricultural systems.

William Bullard (1960s): Excavations uncovered Group A’s pyramids and

burials.

BVAR Project (1990s–present): Led by Dr. Jaime Awe, this

ongoing effort has revealed tombs, causeways, and residential zones,

using LiDAR to map unexcavated areas. A 2016–2017 dig exposed a royal

palace and elite burial, published in Latin American Antiquity.

The

site’s size—comparable to Xunantunich—suggests a population of several

thousand at its peak. Its decline in the Terminal Classic (AD 850–1000)

likely stemmed from drought, warfare, or trade disruptions, common

across the Maya Lowlands. Postclassic activity was minimal, with small

reoccupations.

Baking Pot’s preservation faces challenges.

Looting in the 20th century damaged tombs, and farming has disturbed

outer zones. However, the Belize Institute of Archaeology (NICH)

protects the core, with BVAR restoring key structures. Unlike Caracol’s

polished pyramids, Baking Pot’s mounds are partly overgrown, giving it a

raw, exploratory feel.

The Cayo District, with ~90,000 residents, blends tourism,

agriculture (citrus, bananas), and education (Galen University is

nearby). Baking Pot employs local guides and supports research, though

its low visitor numbers limit economic impact compared to Xunantunich.

The nearby Mennonite community at Spanish Lookout, known for dairy and

poultry, adds a unique cultural layer, with their markets selling fresh

cheese alongside Maya crafts.

Belize’s broader context enhances

Baking Pot’s appeal. As a biodiversity hotspot, the region hosts jaguar

reserves (Cockscomb Basin, 60 miles away) and the Belize Barrier Reef

(UNESCO site, 80 miles east). Belize’s English-speaking status eases

communication, while Kriol and Maya languages reflect its multicultural

soul. Challenges like deforestation and quarrying persist, but Baking

Pot’s protected status ensures conservation, aided by BVAR’s community

outreach, including school programs.

Baking Pot is ideal for those seeking an off-the-grid Maya

experience, with minimal crowds and a sense of discovery. Key details

include:

Access: From San Ignacio, a 15-minute drive on the

George Price Highway leads to a dirt road marked by a small sign. Public

buses to Spanish Lookout stop nearby (~$2 USD), or taxis cost $15 USD

one-way. Guided tours from San Ignacio or Belmopan ($50–80 USD) include

transport and lunch.

What to See:

Group A Plaza: Explore the

main pyramid and eastern shrine, with low mounds revealing temple

foundations. Climb the pyramid for river views.

Group B Palace:

Wander the ballcourt and palace courtyards, imagining elite life.

Unexcavated mounds hint at hidden chambers.

Causeways: Walk the sacbe

to feel the city’s scale, spotting iguanas or parrots.

Riverbank: The

Belize River offers a serene spot to reflect, with canoes sometimes

available from locals.

Tours: Self-guided visits are free (no

entrance fee), but guides (~$20–30 USD) from BVAR or operators like Pacz

Tours add depth, explaining burials and architecture. Tours often pair

Baking Pot with Xunantunich or Barton Creek Cave for a full day.

Facilities: Minimal—no restrooms, visitor centers, or food stalls. Bring

water, snacks, insect repellent, sunscreen, and sturdy shoes. San

Ignacio has hotels (e.g., Cahal Pech Village Resort) and restaurants for

post-visit meals.

Experience: Visitors describe Baking Pot as

“peaceful” and “untouched,” per TripAdvisor reviews, with its jungle

setting evoking adventure. The lack of restoration lets you imagine

archaeologists at work, though some wish for signage. Expect 1–2 hours

to explore, longer with a guide.

Baking Pot is a focused archaeological stop, but the Cayo District

offers complementary experiences:

Xunantunich (10 miles west): A

restored site with the 130-foot El Castillo pyramid, reachable by

hand-cranked ferry.

Cahal Pech (5 miles west): A compact ruin with

elite residences, ideal for history buffs.

Barton Creek Cave (15

miles south): Canoe through a Maya ceremonial cave with stalactites and

pottery.

San Ignacio Market (6 miles west): A Saturday hub for Maya

crafts, Mennonite produce, and Kriol street food like hudut.

Green

Iguana Conservation Project: A sanctuary in San Ignacio for interacting

with iguanas.

Actun Tunichil Muknal (ATM) Cave (25 miles south): A

strenuous trek to a Maya sacrificial site with skeletons and artifacts.

These pair well with Baking Pot, creating a multi-day Cayo itinerary

blending ruins, nature, and culture.