Hours of Citadel

Oct-Mar: Sat-Thu 8am - 4pm

Apr-Sep: Sat-Thu 8am - 7pm

Fri 10am - 4pm

The Amman Citadel, known locally as Jabal al-Qal’a (Arabic for “Citadel Hill”), is one of Jordan’s most significant archaeological and cultural landmarks, perched atop one of Amman’s seven historic hills at an elevation of approximately 850 meters. Located in the heart of the capital, it offers a sweeping panorama of the city’s ancient and modern landscapes. Continuously occupied since the Neolithic period (ca. 8500 BCE), the Citadel encapsulates Jordan’s rich history, from its role as the Ammonite capital of Rabbath-Ammon to its prominence under Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine, and Umayyad civilizations. Home to iconic structures like the Temple of Hercules, the Umayyad Palace Complex, and the Jordan Archaeological Museum, it is a microcosm of Jordan’s cultural evolution.

The Amman Citadel’s history spans over 10,000 years, making it one of

the world’s oldest continuously inhabited sites. Its strategic hilltop

location, offering natural defenses and visibility over trade routes

like the King’s Highway, attracted settlers as early as the Neolithic

period (ca. 8500–5500 BCE), with evidence of early farming communities.

By the Middle Bronze Age (ca. 1800–1550 BCE), it emerged as

Rabbath-Ammon, the capital of the Ammonite Kingdom, a Semitic-speaking

people known for agriculture, trade, and their god Milcom. The Ammonites

fortified the hill, building structures like the recently uncovered

Ammonite palace (2014–2016 excavations), which may date to the 9th–7th

centuries BCE.

During the Hellenistic period (ca. 333–63 BCE),

the city was renamed Philadelphia after Ptolemy II Philadelphus,

reflecting Greek influence. The Romans, annexing the region in 63 BCE,

transformed Philadelphia into a key city of the Decapolis, a league of

ten Greco-Roman cities. The Citadel’s Roman phase, marked by the Temple

of Hercules (ca. 162–166 CE), solidified its religious and civic

importance. Under Byzantine rule (4th–7th centuries CE), the Citadel

housed Christian communities, as evidenced by the Byzantine Church

(5th–6th centuries CE).

The Umayyad period (661–750 CE) saw the

Citadel’s peak as the administrative center of the province of

Al-Urdunn, with the construction of the Umayyad Palace Complex (ca.

720–750 CE), including a governor’s

residence, mosque, and

cistern. A devastating earthquake in

749 CE damaged the complex, and after the Abbasid overthrow of the

Umayyads in 750 CE, the Citadel declined, with sporadic reuse by

Fatimids, Mamluks, and Ottomans. By the modern era, it was largely

abandoned until archaeological interest revived it in the 20th century.

Excavations, beginning in the 1920s under British and French teams

and continuing with Jordanian-Spanish collaborations, have uncovered

layers of the Citadel’s history. The establishment of the Jordan

Archaeological Museum in 1951 and restoration of the Umayyad Palace in

the 1990s have transformed the Citadel into a major tourist and research

site, listed on UNESCO’s tentative World Heritage list since 2014.

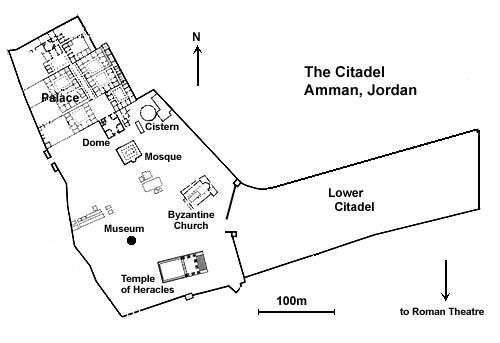

The Amman Citadel is an open-air archaeological complex spanning

approximately 17 hectares, enclosed by fortification walls rebuilt

across multiple periods (Ammonite, Hellenistic, Roman, and Umayyad). Its

architecture reflects a palimpsest of civilizations, with structures

ranging from massive stone temples to intricate Islamic stucco work. The

uneven terrain, shaped by the hill’s natural contours, influenced the

irregular layout of buildings, distinguishing the Citadel from more

planned sites like Jerash.

Key sites include:

Temple of

Hercules (Roman, ca. 162–166 CE):

A monumental Roman temple dedicated

to Hercules, built during the reign of Emperor Marcus Aurelius under

Governor Geminius Marcianus. Located on the Citadel’s southern edge, it

features six surviving Corinthian columns (10 meters tall) from an

original colonnade, set on a podium measuring 43x27 meters.

The

temple’s massive limestone blocks, some weighing over 10 tons, were

quarried locally, reflecting Roman engineering prowess. A partially

preserved statue hand, possibly Hercules’, suggests a colossal cult

statue once stood within.

Its elevated position offered views of the

Roman Theatre below, linking the Citadel to the city’s civic core. The

temple’s ruins, dramatically lit at night, are a focal point for

visitors.

Umayyad Palace Complex (ca. 720–750 CE):

A sprawling

administrative and residential complex built for the Umayyad governor of

Al-Urdunn, covering the Citadel’s northern terrace. It includes:

Monumental Gateway: A cruciform entrance with four vaulted iwans,

restored with a modern wooden dome (1998), used for ceremonial access

and modern cultural events.

Audience Hall (Diwan): A 24x26-meter

cruciform hall, likely a throne room, with stucco ornaments (rosettes,

palmettes) and a modern dome. Built over a Byzantine church, it reflects

Byzantine and Sassanian influences.

Central Courtyard and Souk: A

30x30-meter courtyard with 11 shop-like rooms, connected by a colonnaded

street, facilitating trade and gatherings.

Water Cistern: A

17.5-meter-wide, 5-meter-deep cistern holding 250,000 gallons, with a

central column and stairs, showcasing Umayyad hydraulic engineering.

Umayyad Mosque: A Persian-style mosque south of the palace, oriented

toward Mecca, with a columned prayer hall.

Residential Units: Nine

ruined buildings for the governor’s entourage, built over Roman

foundations.

The complex’s stucco work and recycled Roman materials

highlight Umayyad adaptation of classical styles, though the 749 CE

earthquake left much in ruins.

Byzantine Church (5th–6th

centuries CE):

A small basilica near the Temple of Hercules,

measuring 24x15 meters, with a three-aisled layout, apse, and mosaic

fragments. Built using Roman columns, it reflects Christian worship on

the Citadel before the Islamic conquest.

Its modest size suggests a

local congregation, possibly linked to Byzantine officials or merchants.

The church’s ruins are less prominent but add to the Citadel’s religious

diversity.

Ammonite Remains (Iron Age II, ca. 1000–500 BCE):

Recent excavations (2014–2016) uncovered an Ammonite palace or

administrative building near the Umayyad complex, with massive stone

walls and ceramic evidence dating to the 9th–7th centuries BCE.

Other

Ammonite artifacts, like seals and statuettes, are housed in the Jordan

Archaeological Museum, linking the Citadel to Rabbath-Ammon’s role as a

regional capital.

Jordan Archaeological Museum (1951):

A

modest museum housing artifacts from Jordan’s Paleolithic to Islamic

periods, including Ammonite seals, Roman statues, Byzantine mosaics, and

Umayyad stucco. While some items (e.g., ‘Ain Ghazal statues) moved to

the Jordan Museum in 2014, it remains essential for contextualizing the

Citadel’s history.

Its simple design and dated displays contrast with

the open-air ruins, but it offers a sheltered complement to outdoor

exploration.

Fortification Walls and Gates:

The Citadel’s

walls, rebuilt across periods, enclose the complex, with three main

gates (north, south, and east) connecting to the lower city. Hellenistic

and Roman towers, later reinforced by Umayyads, reflect evolving

defensive needs.

The walls’ limestone blocks, some recycled from

earlier structures, create a cohesive boundary, though parts are eroded

or reconstructed.

The Citadel’s architecture is a layered tapestry,

with Ammonite foundations, Roman grandeur, Byzantine modesty, and

Umayyad sophistication. Restoration efforts, particularly for the

Umayyad Palace, balance preservation with modern use, though modern

additions like wooden domes spark debate over authenticity.

The Amman Citadel is a cultural and historical cornerstone, embodying

Jordan’s role as a crossroads of ancient civilizations. Its significance

includes:

Multilayered History: Spanning Neolithic to Islamic

periods, the Citadel reflects continuous human activity, from early

farming to imperial governance. Its Ammonite, Roman, Byzantine, and

Umayyad phases highlight Jordan’s adaptability to regional powers, as

noted in studies like The Archaeology of Jordan (2001).

Ammonite

Legacy: As Rabbath-Ammon, the Citadel was the political and religious

heart of the Ammonite Kingdom, with recent finds like the Ammonite

palace reinforcing its Iron Age importance. Artifacts in the museum,

such as Milcom statuettes, connect to biblical and regional narratives.

Roman and Byzantine Influence: The Temple of Hercules and Byzantine

Church underscore Amman’s role in the Roman Decapolis and early

Christian Levant, linking it to cities like Jerash and Madaba.

Umayyad Urbanism: The Umayyad Palace Complex, with its mosque, souk, and

cistern, represents an early Islamic “city” model, showcasing

administrative and architectural innovation. Its stucco work influenced

later Islamic art, as seen in mosques across the Middle East.

Tourist

and Educational Hub: A top-rated attraction (Tripadvisor Travelers’

Choice), the Citadel draws global visitors for its history and views,

included in the Jordan Pass and UNESCO’s tentative list. Posts on X

praise its “stunning blend of eras,” reflecting its appeal to history

buffs and photographers.

Cultural Identity: The Citadel reinforces

Jordan’s diverse heritage, complementing modern landmarks like the Abu

Darwish Mosque. It counters narratives prioritizing biblical or

Greco-Roman history by emphasizing local Ammonite and Islamic

contributions, aligning with Jordan’s national identity.

Archaeological Research: Ongoing excavations, supported by the

Department of Antiquities and international teams, continue to uncover

Ammonite and Umayyad structures, advancing knowledge of Jordan’s

pre-Hellenistic and early Islamic periods.

However, the Citadel’s

prominence may overshadow smaller sites like the Ammonite Watch Tower,

and its focus on elite structures (temples, palaces) risks marginalizing

non-elite narratives, such as those of farmers or artisans.

Location: Jabal al-Qal’a, central Amman, Jordan. The Citadel is on

Al-Qal’a St., overlooking the Roman Theatre and downtown.

Access:

Reachable by taxi (request “Jabal al-Qal’a”; ~2–3 JOD from downtown).

Public buses serve Raghadan Bus Station (1.5 km), followed by a

10-minute uphill walk or short taxi ride. Free parking is limited;

arrive early. Walking from downtown is possible but steep (~15–20

minutes).

Opening Hours: Typically 8:00 AM–6:00 PM (April–October),

8:00 AM–4:00 PM (November–March), closed during heavy rain. Friday hours

may be 10:00 AM–4:00 PM. Confirm via https://myjordanjourney.com.

Admission: 3 JOD for non-residents, free for children under 12 and

Jordanian residents with ID. Included in the Jordan Pass (72–80 JOD,

covering Petra, Jerash). Guided tours (~10–20 JOD) via operators like

Jordan Memories (https://jordanmw.com) or Wonders Travel

(https://jordan-travel.com).

Best Time to Visit: Spring (March–May)

or fall (September–November) for mild weather (15–25°C/59–77°F). Early

morning (8:00–10:00 AM) or late afternoon (3:00–5:00 PM) avoids summer

heat (up to 30°C/86°F) and offers golden-hour lighting for photos,

especially of the Temple of Hercules.

Visit Duration: 2–3 hours to

explore the Temple of Hercules, Umayyad Palace, Byzantine Church, and

Jordan Archaeological Museum. Add 1 hour for a guided tour or leisurely

photography.

Nearby Attractions: Roman Theatre (1.8 km), Grand

Husseini Mosque (2 km), Rainbow Street (3 km), Abu Darwish Mosque (2.5

km), Jordan Museum (4 km). Pair with a downtown tour for souks and

eateries like Hashem Restaurant (2 km).

Accessibility Features: The

Citadel’s rocky terrain and steps limit wheelchair access; the museum

and Umayyad Palace’s audience hall are reachable with assistance. Wear

sturdy shoes. Restrooms, shaded benches, and a ticket office are

available, but no food vendors (bring water/snacks).

Tips: Hire a

guide or use an audio guide (available at the entrance) for context, as

signage is informative but brief. Photography is allowed; tripods

require permission. Check for concerts or exhibitions at the Umayyad

gateway via https://www.visitjordan.com. Combine with the Roman Theatre

for a half-day itinerary.

The Citadel’s 360-degree views of Amman’s

hills, Roman Theatre, and skyline are a highlight, especially at sunset.

Visitors often describe it as “a journey through time,” per Tripadvisor

reviews.

While the Amman Citadel is a celebrated heritage site, several

aspects warrant critical examination:

Narrative Imbalance: The

Citadel’s tourism narrative emphasizes Roman and Umayyad periods, with

the Temple of Hercules and Umayyad Palace as focal points, potentially

overshadowing Ammonite and Byzantine contributions. Recent Ammonite

finds are underrepresented in public displays, limiting recognition of

Jordan’s pre-Hellenistic roots.

Restoration Debates: Modern

additions, like the wooden domes on the Umayyad Palace’s audience hall

and gateway (1998), prioritize functionality (e.g., hosting events) but

deviate from original stonework, sparking debate over authenticity

versus tourism needs. The domes are reversible, but some archaeologists

argue for more traditional materials, as noted in The Annual of the

Department of Antiquities of Jordan.

Incomplete Excavation: Much of

the Citadel, including Ammonite and residential Umayyad areas, remains

unexcavated due to funding and urban constraints. This limits

understanding of non-elite life, as artifacts mostly reflect elite

contexts (e.g., temples, palaces), per critiques in The Archaeology of

Jordan.

Accessibility Barriers: The Citadel’s uneven terrain excludes

visitors with mobility issues, despite Jordan’s inclusive tourism goals.

Virtual tours or improved pathways could address this, as suggested in

tourism forums and Reddit discussions.

Urban Encroachment: Amman’s

modern sprawl, with traffic noise and construction visible from the

Citadel, disrupts its historical ambiance, unlike isolated sites like

Qasr Amra. Visitors on X note this contrast, calling it “a gem amidst

chaos.”

Cultural Representation: The Citadel’s focus on Ammonite,

Roman, and Islamic heritage may underrepresent other groups, such as

Nabataeans or pre-Ammonite Bronze Age communities, whose presence is

less documented. A broader narrative could highlight Amman’s

cosmopolitan past, as suggested by scholars like Glenn Corbett.

These

critiques underscore the need for balanced storytelling, further

excavation, and accessibility improvements to maximize the Citadel’s

cultural and educational impact. Digitizing artifacts or hosting

temporary exhibits could elevate its global profile, aligning with

trends at sites like Petra.